Translation: Claudia Lars

Here’s my chapter on Claudia Lars. I found this a hard poem to translate. Though I could’t do it justice, I enjoyed trying. Vanguardist poetry is hard, in general. I think because it is built on so much symbolism from other poems, but is trying to break free of that dependency; it feels like shorthand. Sometimes the poems I like the most, or like the most to translate, don’t come out that well. Maybe it’s overthinking. I’d like very much to translate her little book on Laika the cosmonaut dog.

Of course, I am especially fond of Lars because of my love of feminist science fiction. She’s a little bit science-fictiony, don’t you think? And this is certainly a feminist response to patriarchal poetics — a description of “woman” in poetry, but not with the metaphors and language that describes women in terms that are disempowering. It is possibly a difficult poem for that reason too; because it is trying to evade something.

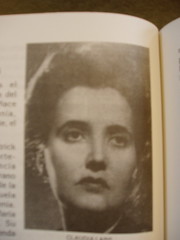

Claudia Lars (1899-1974)

Margarita del Carmen Brannon Vega is her birth name; she is also called Carmen Brannon Beers or Carmen Brannon de Samoya Chinchilla. She was born in El Salvador. She studied and lived in the United States, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Guatemala.

Her early work in the 1920s and 1930s was compared to Agustini, Mistral, Storni, and Ibarbourou. She lists as her early influences Cervantes, Fray Luís de León, Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Góngora, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Burns, Coleridge, Whitman, Poe, Dickinson, Shelley, Byron, Yeats, Blake, and Darío (Barraza 142). Critics called her a lyrical postmodernist. Later, she was considered part of the Vanguard, writing in both formal and free verse.

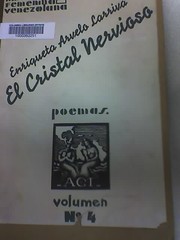

Her books include Tristes mirajes (1916); Estrellas en el pozo (1934), and Canción redonda (1937). She also wrote poems and books for children, sonnets to famous women writers of many countries, and, later in the 20th century, she wrote a poem cycle on the cosmonauts of the United States and Russia–including the dog Laika.

“Dibujo” sets out a bold feminist vision of the future. The poem’s woman “que llega,” who’s coming, arriving now, or will soon arrive, transcends the usual gendered metaphors. Her ascension is not like flight, and not like the growing of a plant that is rooted in the earth. Instead, Lars describes a woman who stands up, who has agency and raises herself up with all her intelligence and power.

Dibujo de la mujer que llega

En el lodo empinada,

No como el tallo de la flor

y el ansia de la mariposa . . .

Sin raíces ni juegos:

más recta, más segura

y más libre.

Conocedora de la sombra y de la espina,

Con el milagro levantado

en los brazos triunfantes.

Con la barrera y el abismo

debajo de su salto.

Dueña absoluta de su carne

para volverla centro del espíritu:

vaso de lo celeste,

domus áurea,

gleba donde se yerguen, en un brote,

la mazorca y el nardo.

Olvidada la sonrisa de Gioconda,

Roto el embrujo de los siglos,

Vencedora de miedos.

Clara y desnuda bajo el día limpio.

Amante inigualable

en ejercicio de un amor tan alto

que hoy ninguno adivina.

Dulce,

con filtrada dulzura

que no daña ni embriaga a quien la prueba.

Maternal todavía,

sin la caricia que detiene el vuelo,

ni ternuras que cercan,

ni mezquinas daciones que se cobran.

Pionera de las nubes.

Guía del laberinto.

Tejedora de vendas y de cantos.

Sin más adorno que su sencillez.

Se levanta del polvo . . .

No como el tallo de la flor

que es apenas belleza.

Sketch of the woman of the future

Standing tall in the mud.

Not like the flower's stalk

and butterfly’s desire . . .

No roots, no flitting,

more erect, more sure

and more free.

Knower of shadow and thorn,

With miracle held high

in her triumphant arms.

With obstacle and abyss.

beneath her stride.

Absolute queen of her flesh

returned to the center of her spirit:

vessel of the celestial,

domus aurea, home of the golden;

clod where shoots burst forth into

maize and fragrant flower.

Forgotten: the Mona Lisa's smile.

Broken: the spell of centuries.

Conquered: the fears.

Bright and naked in the pure, clean day.

Unequalled lover

in enjoyment of a love so lofty

that no one today could predict it.

Sweet,

with controlled sweetness

that doesn't hurt or intoxicate the drinker.

Maternal still,

without the caress that holds back flight

nor tenderness that traps,

nor submission and giving in, that little by little, smothers.

Pioneer of the clouds.

Guide to the labyrinth.

Weaver of veil and song.

Adorned only in her simplicity.

She stands up from the dust . . .

Not like the flowering stem

that’s not so beautiful.